How Much Money to Raise at the Seed Stage

Learn how much money to raise at the seed stage using a clear, step-by-step process based on milestones, runway, costs, and risk.

Founders ask, “How much money to raise at the seed stage?” and then Google the average seed round sizes.

The problem is simple:

Internet numbers do not know your product cycle, hiring needs, sales motion, or risks.

If you copy a “typical seed round size,” you might raise too little and run out of cash before real proof shows up or raise too much and create avoidable dilution and pressure.

A strong seed ask is not a trend. It is a milestone-backed budget with a clear runway and a clear use of funds. Investors do not need you to be perfect.

They need you to be specific, realistic, and consistent:

- This is what we will achieve,

- This is what it costs,

- And this is how long it takes.

Below is a simple process you can reuse for any seed round, in any country.

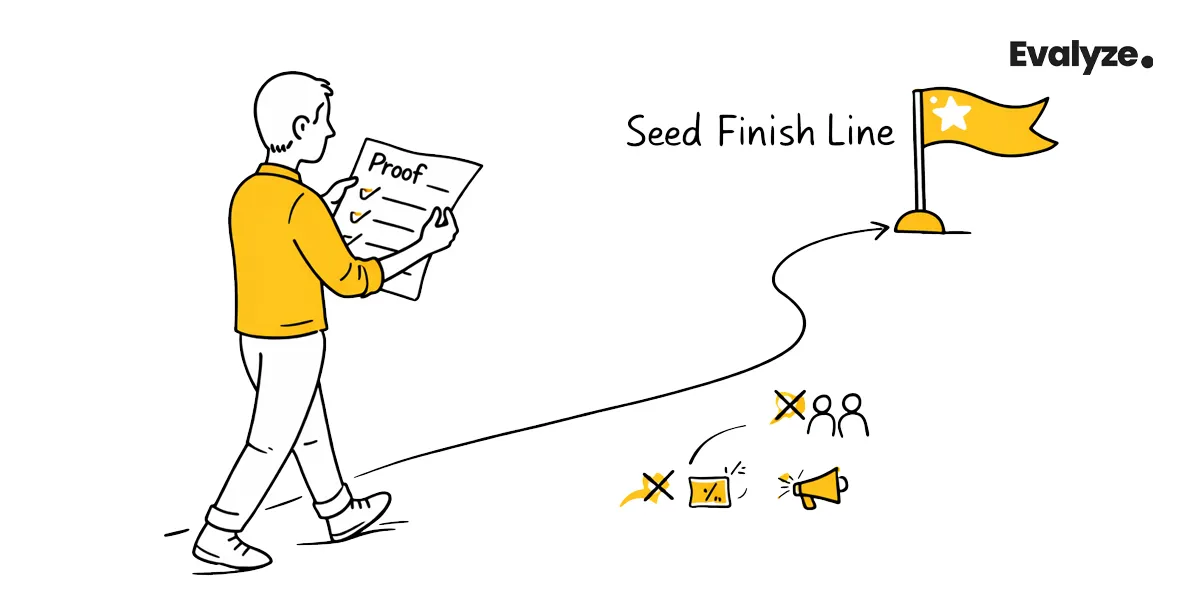

Step 1: Define the “Seed Finish Line”

Choose the milestone your seed must unlock

Seed funding is supposed to buy you time and resources to reach a meaningful next step. That next step is your finish line for the round.

Your finish line should answer one question:

What proof will make the next round easier (or make us sustainable without one)?

Examples of seed milestones (to Series A) by business model:

- B2B SaaS (subscription):

- Prove repeatable demand and retention: customers stick, expand, and pay reliably.

- Show a sales motion you can scale: a clear ICP, a repeatable pitch, and predictable pipeline creation.

- Marketplace or network business:

- Prove liquidity in a tight niche: users come back because the market “works.”

- Show improving unit economics: take rate and contribution margin improve as volume grows.

- Developer tools or product-led growth (PLG):

- Prove activation and retention: users adopt the product and keep using it.

- Show a path to monetization: conversion points are clear and improving.

- Regulated (health, fintech, security):

- Prove compliance readiness and reduced regulatory risk.

- Validate that distribution is possible: partnerships, pilots, approvals, or audits move forward.

A good finish line is not “grow users” or “build features.” It is a clear business outcome that reduces investor doubt.

Recommended for you: How Much Money Do You Need To Raise At The Pre-Seed Stage?

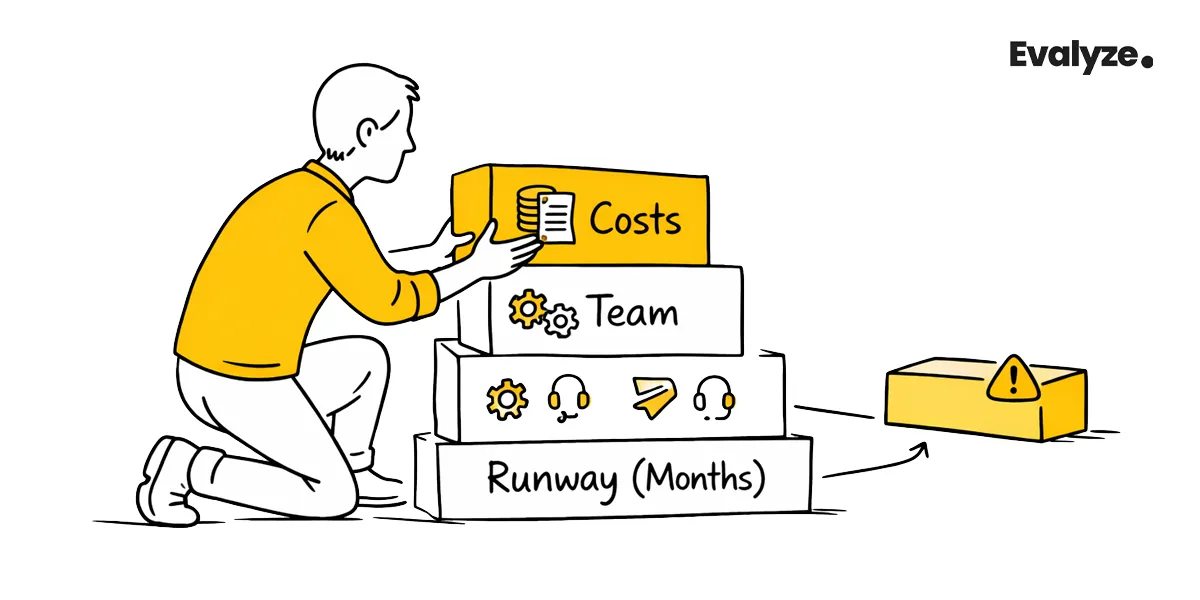

Step 2: Build a Bottom-Up Plan

Pick a runway window that matches your cycle time

Seed runway is how long your cash lasts, measured in months. There is no universal correct number. You choose a runway based on how long it takes for your finish line to reach.

A practical way to choose:

- How many months will it take to build what’s required?

- How many months to sell it (or deploy it)?

- How many months to prove it’s working (retention, repeatability, outcomes)?

If you sell to enterprises, your cycle may be longer. If you’re regulated, timelines are longer. If you are product-led and self-serve, cycles can be shorter.

Trade-offs:

- Short runway (e.g., ~12-15 months): Forces focus, but leaves little room for delays.

- Medium runway (e.g., ~15-18 months): Often enough to hit targets with some buffer.

- Long runway (e.g., ~18-24 months): Can reduce fundraising frequency, but increases time to prove urgency and can increase dilution if valuation does not move.

Choose runway like an operator, not like a gambler.

Map the minimum team required to hit the targets

Your seed round should fund the minimum team that can reach the finish line. Founders often over-hire because it feels like progress. Investors often worry about over-hiring because it creates burn that is hard to reverse.

Build your team plan by roles and timing:

- What roles are essential in months 1-6?

- What roles are only needed after early signals exist?

- Which work can be done by contractors for now?

Typical role buckets:

- Product & engineering: build, ship, maintain reliability.

- GTM (go-to-market): sales, growth, marketing, partnerships.

- Customer success/support: keep customers and reduce churn.

- Ops/finance/legal: keep the business safe and running.

Avoid hiring “nice-to-have” roles early (heavy management layers, brand teams, large admin functions) unless your model truly demands it.

Estimate fully-loaded costs (not just salaries)

Your budget must use fully-loaded cost, not base salary. Fully-loaded cost includes:

- Salary or contractor rate

- Taxes and benefits (varies by country)

- Equipment and software

- Recruiting costs

- Management overhead and onboarding time

A simple rule:

If you cannot explain how you estimated costs, investors will assume the number is optimistic.

Add operating costs, and founders consistently forget

These line items often surprise founders:

- Cloud and data costs (which rise with usage)

- Legal, accounting, and fundraising-related fees

- Compliance and security tools (especially B2B)

- Insurance (cyber, liability, employee-related)

- Customer support systems and success tools

- Travel for enterprise deals or partnerships

- Payment fees, refunds, chargebacks (if relevant)

Write them down. Then be honest about what grows with scale.

Practical guide: Fundraising Automation for Startups

Step 3: Convert the Plan into a Seed Funding Amount

The core formula (cash needed)

Your seed funding amount should come from a simple structure:

Total Cash Needed = Ramping Burn + Fixed Costs + One-Time Costs + Buffer

What each term means:

- Ramping burn: your monthly spend changes as you hire and scale.

- Fixed costs: costs you pay regardless (tools, rent, minimum cloud, basic services).

- One-time costs: legal setup, audits, major integrations, certifications, special hires.

- Buffer: planned risk coverage (not random extra money).

If your burn changes over time, do not use one monthly burn number. Build a month-by-month view. It can be simple: 18 rows in a sheet is enough.

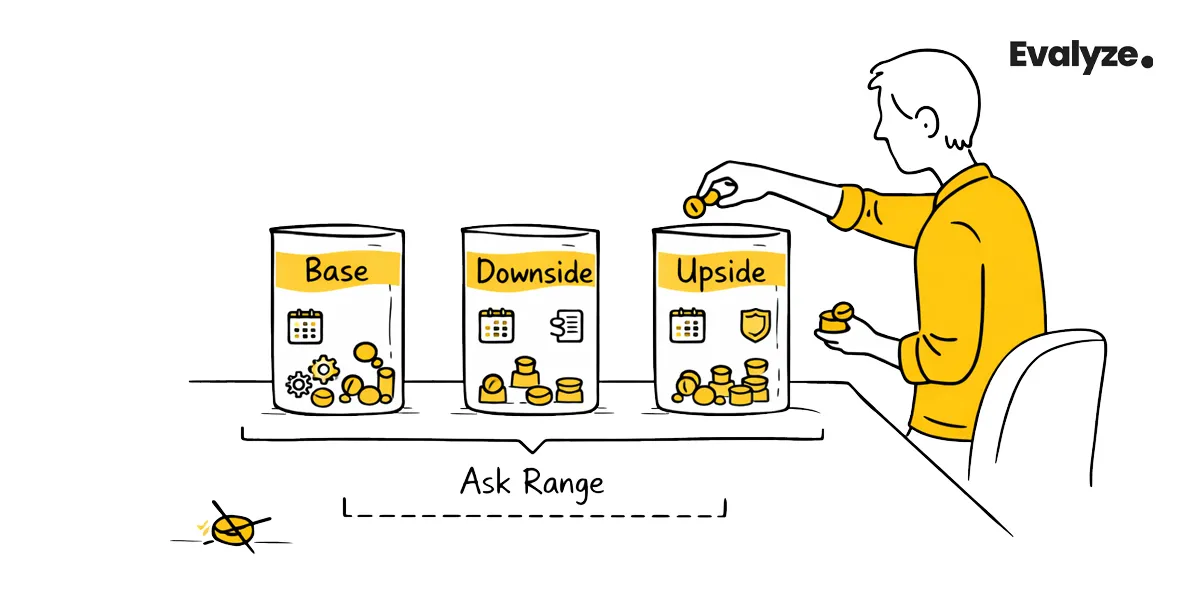

Build 3 scenarios: Base / Downside / Upside

Investors trust founders who plan for reality.

Create three scenarios:

- Base case: expected hiring speed and expected sales cycle.

- Downside case: hiring is slower, sales cycles are longer, or conversion is lower.

- Upside case: stronger pull; you choose to accelerate.

For each scenario, decide in advance:

- What changes in cost?

- What changes in the timeline?

- What gets cut first in the downside?

That last point matters. If you cannot explain what you would cut first, your plan is not prioritized.

Your output should be an ask range, not one fragile number.

For example: “We’re raising $X-$Y depending on how quickly we scale GTM after product validation.” The range must still be tied to a clear plan, not vague flexibility.

Save this for later: How to Build an Investor Funnel + Template

Step 4: Stress-Test Your Ask

The timeline reality check

Most seed plans fail on time, not on talent. Stress-test your plan for:

- Hiring delays (great candidates take time)

- Onboarding time (new hires are not productive on day one)

- Sales cycle length (especially for enterprise)

- Integration lead time (partners and platforms move slowly)

- Regulatory or security reviews (often longer than expected)

If one delay breaks your runway, you are under-raising.

The “buffer” rule

A buffer is not “just in case.” It should cover known risks such as:

- Hiring taking 2-3 months longer than planned

- Needing an extra iteration of the product for retention

- Slower pipeline conversion for the first sales hires

- Unexpected compliance requirements

The key is to say what the buffer is for. Investors are fine with buffers when they are logical.

The dilution sanity check

You do not need a full ownership lecture in a seed-budget post. But you do need to avoid regret.

Ask yourself:

- If we raise this amount, are we likely to give up more ownership than we’re comfortable with at seed?

- Does this amount require a valuation that is unrealistic for our current proof?

- Will a bigger round increase expectations faster than we can deliver?

Your seed ask should protect your ability to raise again, not trap you.

From the founder toolkit: Pre-Seed Fundraising Checklist

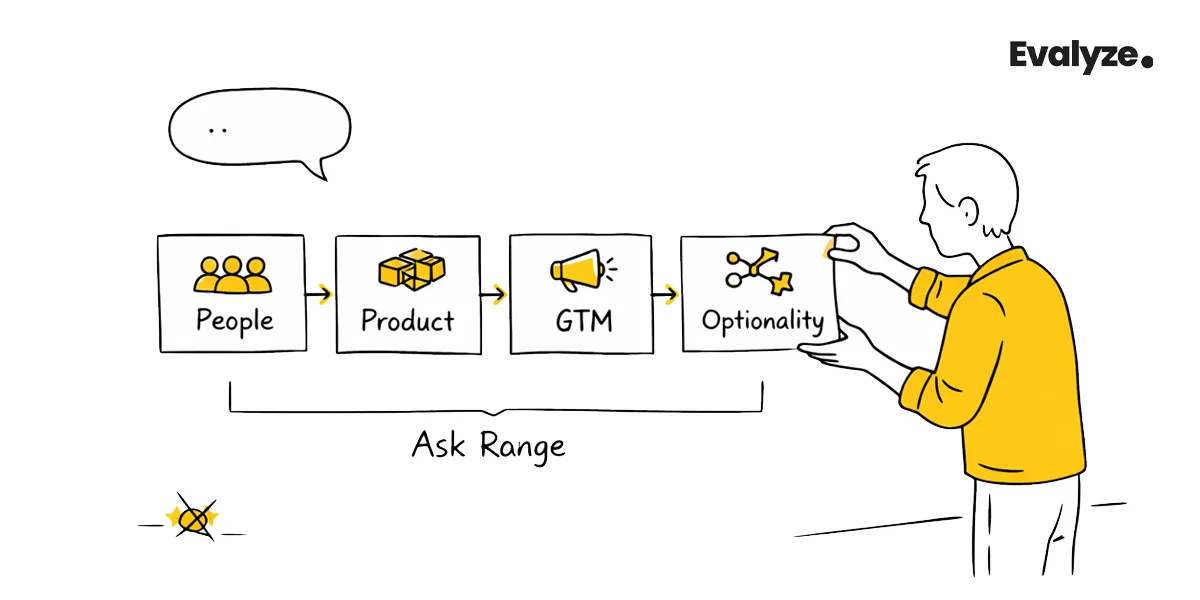

Step 5: Turn the Amount into an Investor-Ready “Use of Funds” Story

Use of funds seed round

A clean “use of funds” is not a pie chart. It is a logical chain:

People → Product → GTM → Proof → Optionality

- People: which roles will you hire and why they map to targets.

- Product: what must be built to enable adoption and retention.

- GTM: how you will acquire customers (channels, sales motion, pipeline).

- Proof: which targets you expect to hit and when.

- Optionality: what you can do if the upside hits (expand markets, scale faster).

Say the ask the way investors want to hear it

Your ask should be one sentence that links money to outcomes:

“We’re raising $X to get Y months of runway and achieve Z targets that unlock our next round.”

Then you support it with:

- The monthly burn ramp

- The milestone list (5-8 targets)

- The hiring plan by quarter

- The scenario plan (base/downside/upside)

Common red flags

Investors get nervous when they see:

- Over-hiring early: too many roles before proof exists.

- Unclear milestones: “growth” without measurable proof.

- Mismatched runway: long runway but no clear plan for proof points.

- Nice-to-have spending: branding, offices, and events before outcomes.

- Math that doesn’t tie out: costs that are missing or too optimistic.

Prevent these by keeping the plan focused and easy to audit.

Don’t miss this: 20 AI Fundraising Tools for Startups

Founder Worksheet: Questions to Answer Before You Name a Number

Use these questions to build your seed fundraising strategy and avoid guessing:

- What is the single milestone that makes the next round (or profitability) easier?

- Which 5-8 targets prove you hit it?

- What roles are truly required, and in which months?

- What is your month-by-month burn rate and runway as the team ramps?

- What are the three biggest risks, and what budget line mitigates each?

- If you raise only 70% of your target, what do you cut first without killing the plan?

If you can answer these clearly, you will sound like a founder who can execute.

Conclusion

The right seed raise is not the number you saw in a tweet. It is a clear answer to what proof you will deliver, how long it will take, and what it will cost, with realistic risk coverage.

If you do the work, finish line, measurable targets, bottom-up budget, three scenarios, and a clean use-of-funds story, you will stop sounding like someone asking for money and start sounding like someone buying outcomes.

FAQ

1. How much seed funding do I need if I’m pre-revenue?

Pre-revenue does not mean you cannot raise seed. It means your proof must be different. You may be proving retention, pipeline, pilots, usage depth, or regulatory progress.

Build the budget the same way: finish line → targets → team → costs → scenarios.

Your seed funding amount should still be tied to milestones, not revenue alone.

2. How do I decide between 15, 18, and 24 months of seed runway?

Choose the runway based on the cycle time. If your product, sales, and proof cycles require longer cycles (enterprise, regulated, complex onboarding), you may need more runway. If your loops are fast (self-serve, quick iteration), you can run leaner. The best runway is the one that gets you to the proof with room for delays, without turning the round into comfort money.

3. Should I raise more now to avoid a bridge later?

Sometimes, but not always. A larger seed can reduce fundraising distraction, but it increases pressure and potential dilution. The better rule is this: raise enough to hit the next meaningful proof point with a real buffer. If your plan needs “more,” mainly because timelines are uncertain, fix the plan or tighten the milestone; do not only increase the number.

4. How do I justify my seed funding amount if it’s above “typical” numbers?

Do not argue with benchmarks. Explain the cost of your finish line. If you are regulated, enterprise, or infrastructure-heavy, show why the proof requires more time and specific hires. Investors will accept a larger number when it is tied to a believable milestone plan and when fund use is disciplined.

More Articles

How Much Money Do You Need To Raise At The Pre-Seed Stage?

Learn how to calculate your pre-seed funding ask using runway, burn rate, milestones, and market benchmarks.

February 7, 2026

Pre-Seed Fundraising Checklist: Investor-Ready Signals

A practical pre-seed fundraising checklist, readiness scorecard, traction milestones, cheque sizes, investor types, SAFE terms, and pitch focus, plus a clean plan.

January 7, 2026